The Impact of Fair Trade on Social and Economic Development a Review of the Literature

The Economic science of Fair Merchandise

Fair Trade certification, a labeling initiative that offers amend terms to producers and helps them to organize, aims to offering ethically minded consumers the opportunity to help lift producers in developing countries out of poverty. In a series of recent papers, I have examined the causes and consequences of Fair Merchandise certification.ane

The appeal of this initiative is reflected in the impressive growth of Fair Trade-certified imports over the past two decades. Since Fair Trade's inception in 1997, sales of its certified products have grown exponentially. In 2016, when data are last available, there were over 1,400 Fair Merchandise-certified producer organizations worldwide representing more than ane.6 million Fair Trade-certified farmers and workers in 73 countries across 19 product categories.

This growth appears to exist driven past socially motivated need by Western consumers who are willing to pay more than for coffee that is produced in a fashion consistent with Fair Trade certification. A number of recent studies focusing on java provide convincing evidence that the demand for Fair Trade-certified products is significantly higher and less price-sensitive than for conventional products.ii

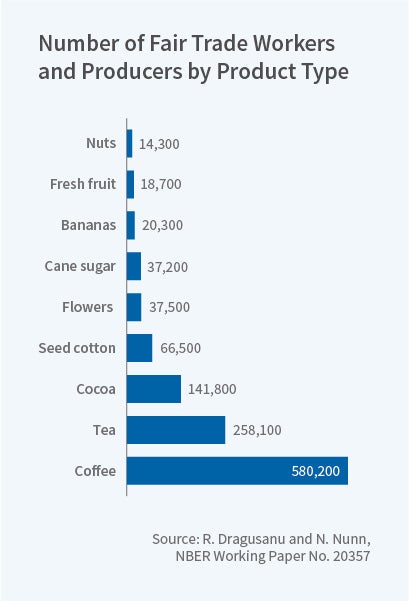

Among the products that take Fair Merchandise certification, coffee is the largest product category. A comparison of coffee with other products in terms of the number of producers that fall under the certification is shown in Figure one. Off-white Trade accounts for 48 percentage of all Fair Merchandise farmers and for 46 percentage of full premiums paid.3 Given this, my enquiry has tended to focus on this sector.

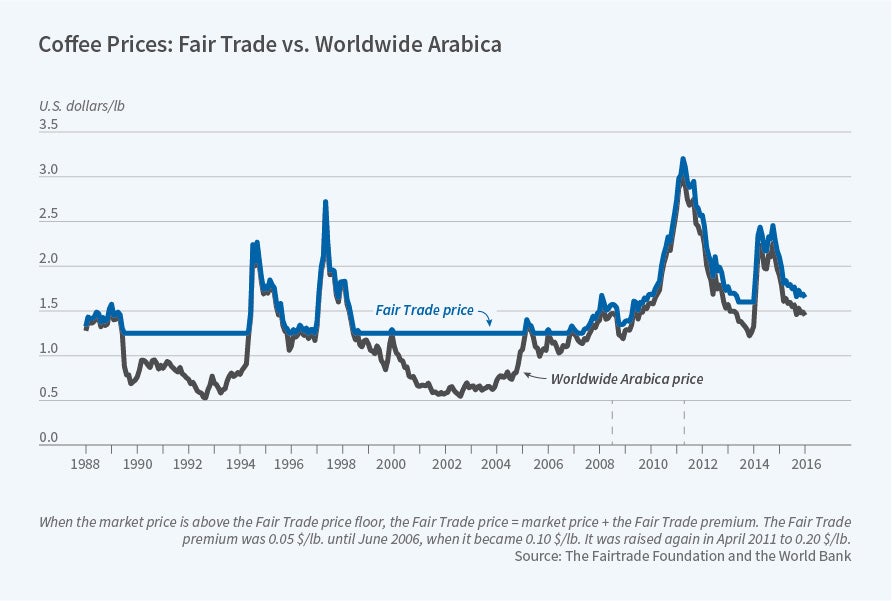

Fair Trade uses two principal mechanisms in an endeavor to achieve its goal of improving the lives of farmers in developing countries. The first is a guaranteed minimum price to be paid if the production is sold as Fair Trade. This is meant to cover the average costs of sustainable production and to provide a guarantee that reduces the adventure faced by coffee growers. The second is a price premium paid to producers. This premium is in addition to the sales price and must exist fix aside and invested in projects that improve the quality of life of producers and their communities. The specifics of how the premium is used must be reached in a democratic fashion past the producers themselves.

The relationship betwixt the sum of the minimum price and price premium — the guaranteed amount that Fair Merchandise-certified producers receive if their products are sold every bit Fair Merchandise — and the market price is shown in Figure 2 for coffee. From the effigy information technology is clear that the market price for coffee has historically been volatile and that, for pregnant periods of time, the market place toll has been beneath the Fair Merchandise cost.

Despite the rapid growth and pervasiveness of Fair Merchandise products, well-identified show of the effects of Fair Merchandise certification remains scarce. The question remains: Does Fair Trade accomplish its intended goals? Does it really work? My recent report with Raluca Dragusanu attempts to answer this question by estimating the effects of Fair Trade certification within the coffee sector in Republic of costa rica.4

The primary issue one faces when attempting to identify the causal effects of Off-white Merchandise is that certification is endogenous. For case, mills may get certified when they as well obtain a lucrative long-term contract from a large buyer like Starbucks. To gain a better understanding of the nature of selection into certification, in August 2012 nosotros interviewed several Fair Trade-certified coffee cooperatives to collect information on the factors that lead co-ops to become Fair Trade-certified. Chiefly, and perhaps surprisingly, nosotros learned that the reasons for selection appear to be ambiguous or even negative. In theory, positive choice could arise, since those with the greatest chapters to adopt Off-white Merchandise are also capable in other dimensions of business organization. However, in reality, the near mutual narrative during our interviews was that Fair Trade was something that producers resorted to only if they had difficulty selling their coffee otherwise.

The written report examines the universe of coffee mills in Costa Rica, observed annually over a sixteen-year flow, 1999–2014. The analysis accounts for time-invariant differences across mills, every bit well as mill-invariant differences across years. Despite accounting for these factors, it is notwithstanding possible that pick into certification results in misleading estimates of the causal effect of Fair Merchandise certification. Thus, the estimation strategy also exploits the fact that the expected benefits that accrue because of Fair Trade certification varied significantly during our sample period. This is true both considering of variation in the market price of conventional coffee and in the price paid for Fair Trade-certified coffee due to changes in the Fair Trade minimum price and price premium. This generates time variation in the price divergence between Fair Trade and conventional coffee, which the report also exploits.

The estimates indicate that when the price flooring is bounden, Fair Trade-certified producers sell their products at higher prices and earn more revenues. Thus, Fair Merchandise does take some effect. However, we also find that the result of Fair Trade is limited to just a fraction of the market: non all coffee that is eligible to be sold every bit Fair Trade can actually be sold every bit Fair Trade by Fair Trade-certified farmers.5 The magnitude of our estimates is consequent with this fact. Taken at face value, they signal that only 12 percentage of Fair Merchandise-eligible coffee was sold as Fair Trade over our sample period. Put differently, we observe that if the constructive price do good to Fair Trade certification — the difference between the Off-white Merchandise and conventional prices — increases by 1 cent, the boilerplate price benefit received by Fair Trade-certified mills is just 0.12 cents.

We then turn to upstream furnishings and approximate the effects of Fair Trade certification on intermediaries, farmers, and farm employees. We link Off-white Trade certification to these individuals, observed in household survey data, by constructing a mensurate of the share of exports in a county (an administrative region in Costa Rica) and year that is from Off-white Merchandise-certified producers.

Since one of the explicit goals of Fair Trade is to set aside funds for community projects, it is possible that households non directly involved in java production, but living in the same canton, may too do good from an increase in Fair Trade certification. Thus, our analysis checks for the presence of spillovers past examining the effects of Fair Trade certification on all households in a canton, including those not employed in the coffee sector.

Nosotros notice no evidence of positive spillover furnishings from Fair Trade certification to households in the county not working in the java sector. For those working inside the java sector, we find sizeable, highly uneven benefits.

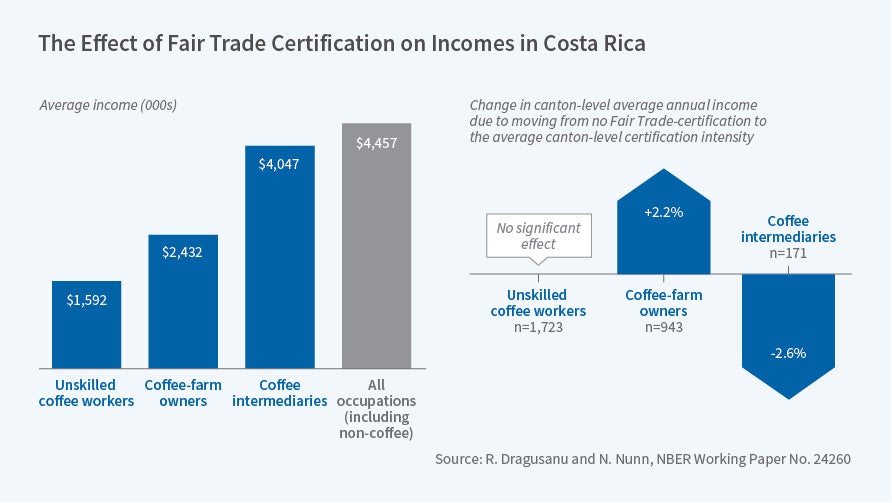

Within the coffee sector, nosotros separately gauge the effects of Fair Trade on the incomes of three groups. The starting time is skilled java growers, who are primarily farm owners and are 33 percent of those working in the coffee sector. The 2nd is unskilled workers, such every bit coffee pickers and farm laborers. This is the largest grouping, accounting for 61 per centum of those working in the sector. The third is non-farm occupations in the coffee sector, primarily intermediaries and their employees who are responsible for transportation, storage, and sales. This grouping accounts for 6 per centum of those working in the sector. The size and average annual income of each group in our sample are summarized in Figure 3. The figure also summarizes the estimated effects for each group.

We detect large positive income furnishings for subcontract owners. An increase from zero to the hateful Fair Trade-certification intensity is associated with a ii.2 percent increase in average income. Given that this grouping is one-third of those working in the java sector, this is a sizeable benefit that affects a big number of individuals. However, we too find that for unskilled workers, the poorest and largest grouping within the coffee sector, there is no evidence of a positive effect of Fair Trade on incomes. The estimated effects for this grouping are small and statistically insignificant. Lastly, we find that the small group of intermediaries in nonfarm occupations is hurt significantly by Fair Trade. For this group, the same increment in Fair Merchandise intensity is associated with a 2.6 percent decline in boilerplate incomes. Since intermediaries have incomes that are approximately 40 percent college than those of farm owners, a consequence of Fair Trade is that information technology decreases income inequality within the coffee sector by transferring rents from higher-income intermediaries to lower-income farm owners.

According to our estimates, virtually 10 percent of the gains to farm owners are likely due to the losses to intermediaries, while the remaining 90 percent of the gains are explained past the minimum cost of Fair Trade-certified coffee. The magnitudes of our estimated effects line up very closely with expected benefits to Off-white Trade, based on actual sales by Off-white Trade-certified producers, the departure between the world price and the Fair Trade toll guarantee, and the number of coffee producers, workers, and intermediaries in Costa Rica during our sample period.

Motivated by the fact that inside Costa rica, cooperatives unremarkably use Fair Trade premiums for building schools, purchasing materials, and providing scholarships, nosotros too examine the effect of Fair Trade certification on instruction, every bit measured by the enrollment of school-aged children. Withal, we find no evidence of positive effects of Fair Trade on schooling. The one education effect of Fair Trade that we exercise find is adverse: For the children of intermediaries, Off-white Trade certification is associated with a 7.3 per centum-point decrease in the probability of loftier school enrollment. These effects are likely due to the large negative income effects that nosotros notice for coffee intermediaries.

In the end, our household estimates pigment a mixed picture. Fair Merchandise appears to accept helped farm owners, increasing their incomes. Role of these gains (approximately ten per centum) appears to arise from a transfer of rents from intermediaries. This is likely due to the creation of farmer cooperatives that perform many of the activities that intermediaries would otherwise perform. As a consequence, Fair Trade is also associated with a significant reduction in the incomes of intermediaries in the coffee sector. Past these metrics, Fair Merchandise appears to be accomplishing some of its stated goals. The relatively impoverished java farmers gain at the expense of the wealthier coffee intermediaries. Nonetheless, we as well find that the poorest and largest grouping within the java sector — unskilled workers — does not gain at all from Fair Trade. In improver, we notice no evidence of positive spillovers of benefits to those in the local community who work exterior of the java sector.

Nigh the Author(s)

Source: https://www.nber.org/reporter/2019number2/economics-fair-trade

0 Response to "The Impact of Fair Trade on Social and Economic Development a Review of the Literature"

Post a Comment